Must Listen

- Satan's Ambition

- Counterfeit Christianity

- The Challenge Of Bible Christianity Today

- Three Men On The Mountain

- Greatest Single Issue of our Generation

- Bob Creel The Death Of A Nation

- Earth's Darkest Hour

- The Antichrist

- The Owner

- The Revived Roman Empire

- Is God Finished Dealing With Israel?

Must Read

- Mysticism, Monasticism, and the New Evangelization

- That the Lamb May Receive the Reward of His Suffering!

- The Spirit Behind AntiSemitism

- World's Most Influential Apostate

- The Very Stones Cry Out

- Seeing God With the New Eyes of Contemplative Prayer

- Is Your Church Doing Spiritual Formation? Pt. 1

- Is Your Church Doing Spiritual Formation? Pt. 2

- Is Your Church Doing Spiritual Formation? Pt. 3

- Is Your Church Worship More Pagan Than Christian? [excerpts]

- The Final Outcome of Contemplative Prayer

- The Conversion Through the Eucharist

- Frank Garlock's Warning Against Vocal Sliding

- Emerging Church Change Agents

- Emerging Church Spreading By Seasoning

- The Invasion of the Emerging Church

- Rock Musicians As Mediums (Excerpts)

- Rick Warren Calls for Union

- Does God Sanction Mystical Experiences?

- Discernment or Criticism?

- Getting High on Worship Music

- Darwin's Errors Pt. 1

- Rick Warren and Rome

- Why are There so Many Races?

- The Drake Equation

- Pathway to Apostasy

- Ironclad Evidence

- Creation Vs. Evolution

- The New Age, Occultism, and Our Children in Public Schools

- A War on Christianity

- Quiet Time

- The System of Babylon

- Is the Bible Gods Word?

- Mid-Tribulation Rapture?

- Churches Forced to Confront Transgender Agenda

- Ironside on Calvinism

- The Purpose Driven Church

- Contemplative Prayer

- Calvinisms Misrepresentations of God

- Babylonian Religion

- What is Redemption?

What Art Thinks

- The Coming of Antichrist

- The Growing Evangelical Apostasy

- Obama's Speech on Religion

- Be Ready

- Rick Warren is Building the World Church

- Spanking Children

- A Lamentation

- Worship

- Elect According to Foreknowledge of God

- Why Do The Heathen Rage

- Persecution and Martyrdom

- The Mystery of Iniquity (or Why Does Evil Continue to Grow?)

- Whatever Happened to the Gospel ?

- Quiet Time

- Divorce and Remarriage

- Ecumenism - What Is It?

- The Premillennial ? Pretribulation Rapture (2 Thessalonians 2)

- Right Now!!

- Misguided Zeal

- You're A Pharisee

- Contemplative Prayer

- NEWSLETTER Dec 2019

- NEWSLETTER Jan. 2020

- Fellowship With Your Maker

- Saved and Lost?

- Security of the Believer

- The Gospel

- NEWSLETTER April 2020

- The Believer Priest

- _Separation

- Elect According to the Foreknowledge of God

- The Preservation and Inspiration of the Scriptures

- Replacement Theology

- The Fear of the Lord

- Two Things That are Beyond Human Comprehension

- Knowing God

Pre-Millennialism

- PreTrib. Rapture

- Differences Between Israel and the Church

- 15 Reasons Why We Believe in the Pre - Tribulation, Pre-millennial Rapture of the Church

- The Pre-Tribulation, Pre-millennial Rapture of the Church

- Yet Two Comings of Christ ?

- Hating the Rapture

- Mid-Tribulation Rapture?

- The Pre - Tribulation Rapture of the Church

- The Error of a Mid-Tribulation Rapture and wrong Methods of Interpretation

- The Power of the Gospel

- Why We Believe in the Premillennial Pretribulation Rapture of the Church

Today's Headlines

- Sorry... Not Available

Locally Contributed...

Audio

- Satan's Ambition

- Counterfeit Christianity

- Three Things We All Must Do

- Two Coming Rulers

- Why No Joy

- Message Of Encouragement

- Greatest Single Issue of our Generation

- salvation.

Video

- One World Religion

- Atheism's Best Kept Secret

- Milk From Nothing

- Repentance and True Salvation

- Giana Jesson in Australia - Abortion Survivor - Pt. 1 & Pt 2

- Billy Graham Denies That Jesus Christ is the Only Way to the Father

- Emerging Church & Intersprituality Preview

- Israel, Islam and Armageddon 6 Parts

- Blasphemous Teachings of the 'emergent Church

- Megiddo 1 - the March to Armageddon

- It's Coming, the New World Order

- Creation Vs Evolution Part 1 of 4

- Creation Vs. Evolution Part 2 of 4

- Creation Vs. Evolution Part 3 of 4

- Creation Vs. Evolution Part 4 of 4

- Billy Graham Says Jesus Christ is not the Only Way

- Wide is the Gate

- A Debate: Mariology: Who is Mary According to Scripture?

- The Awful Reality of Hell

- Conception - How you are Born - Amazing

- Atheist's Best Kept Secret

- Why Kids are Becoming Obsessed With the Occult

- Searching the Truth Origins Preview 2

- Searching for Truth for Origens Preview 1

- Searching the Truth for Origins 3

- Emerging Church & the Road to Rome

- Another Jesus 1 of 7

- Another Jesus 3 of 7

- Another Jesus 4 of 7

- Another Jesus 5 of 7

- Gay Marriage is a Lie - to Destroy Marrriage

- Another Jesus 6 of 7

- Another Jesus 7 of 7

- Evolution Fact or Fiction - Part 1

- Evolution Fact or Fiction - Part 2

- Evolution Fact or Fiction - Part 3

- The Most Heartrending Abortion Testimony You ll Ever Hear, from a Former Abortionist

- Creation vs. Evolution

- A Lamp in the Dark: Untold History of the Bible - Full Documentary

- When the Trumpet of the Lord Shall Sound

Special Interest

- Will the Real Church Please Stand Up?

- Destruction of Damascus?

- Peace and Safety?

- The Emerging Church

- The Growing Evangelical Apostasy

- The State of the Church

- Child Sacrifice

- Outside the Camp

- The Church Walking With The World

- The Present Apostasy

- The World is to Blame

- How to Give Assurance of Salvation Without Conversion

- New Evagelicalism

- New Neutralism Ch. 1 - 3

- New Neutralism Ch 10-11

- New Neutralism Ch 12-13

- New Neutralism Ch 4 -6

- New Neutralism Ch 7 - 9

- The Danger of the Philosophy of New Evangelical Positivism

- Who Do Jehovah's Witnesses Say Jesus Is?

- A Dilemma of Deception: Erwin McManus 'Barbarian Way'

- Are We Fundamentalist

- Contemporary Christian Music Sways Youth to Worldly Lifestyles, Doctrinal Confusion

- The Seventh Commandment

- What will be Illegal When Homosexuality is Legal

- Christ Died on Thursday

- Military Warned 'Evangelicals' No. 1 Threat

- New Age Inroads Into the Church

- Over a Billion Abortions Committed Worldwide Since 1970: Guttmacher Institute

- The Old Cross and the New

- Is Pope Francis Laying the Groundwork for a One World Religion?

- The Goal is to Destroy all Culture and the Constitution

- E - Bomb the Real Doomsday Weapon

- The Eigtht Commandment

- Muslim Brotherhood Inside American Colleges

- Scholars Trying to Redefine Inerrancy

- In Jesus Calling: Jesus Contradicts Himself

- Jesus Calling Devotional Bible? Putting Words in Jesus Mouth and in the Bible

- How the Quantum Christ Is Transforming the World

- Creation Vs. Evolution: Could the Immune System Evolve?

- Cessationism

- Was Noah's Flood Global or Local?

- Isn't Halloween Just Harmless Fun?

- Rock Music and Insanity (Excerpts)

- Preview of the Coming of the One World Religion for Peace:

- Muslims Invoke the Name of Jesus?

- A Sin Problem Rather Than a Skin Problem

- Scientific Evidence for the Flood

- Another Step to Rebuilding the Temple - Holy of Holies Veil Being Recreated

- Darwin's Errors Pt. 1

- Eastern Mysticism

- George Muller's rules for discerning the will of God

- The Tract

- The Church and the World Deceived

- Ye Must Be Born Again

- The Call of Abraham

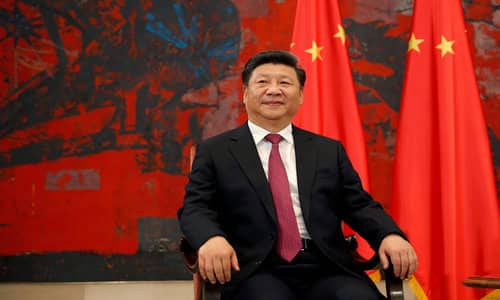

by BILL POWELL/NEWSWEEK

March 7th, 2018

It was a bland, bureaucratic statement—but its implications could be profound. In late February, China’s Communist Party announced a proposal to abolish term limits for its highest office. The party hasn’t made a final decision, but the news seemed to confirm what many have long suspected: Xi Jinping, the country’s leader, wants to be president for life.

The announcement wasn’t surprising, but many didn’t expect it to come so soon. Aside from being president, Xi is also the general secretary of the Communist Party and commander in chief of the country’s armed forces. The term limits on his presidency effectively constrain his ability to hold the other two jobs. Since Xi took office in March 2013, he’s been consumed with his fight against corruption. This battle is basically a proxy for him and his allies to consolidate control over the highest levels of the party, as well as big state-owned companies. In Chinese politics, personal rivalries and differing agendas are rarely visible to the outside world. So many had assumed Xi’s fight was still ongoing, given how deeply entrenched corruption is in China.

If the party does decide to end term limits for president, it could have major implications for the nation—and the world. Domestically, it would rupture what has been a stable system of succession. Deng Xiaoping, the father of China’s economic reforms, created that system in 1982. Prior to Deng’s rule, China was mired in the chaos and pain of the Cultural Revolution, when Mao Zedong “had absolute power over the lives and deaths of others,” wrote Mo Zhixu, a political commentator in Guangzhou.

Post-Mao, Deng and his successors transformed China from an isolated, impoverished country into the second most powerful nation in the world. Many believe the country will inevitably surpass the United States in terms of influence and economic growth. But Beijing has experienced these changes during a period of relative stability, when political transitions came to be seen as orderly, predictable. Deng’s successor, Jiang Zemin, handed power to Hu Jintao, who after a decade turned the party over to Xi. That predictability is now in question.

What’s not in question is that Xi wants to increase his country’s clout, to show the world that his model of government is a worthy alternative to those of the West. Despite American resistance, Xi shows no sign of backing away from his efforts to dominate in the South and East China Seas. He has also extended his country’s influence to the south and west, all the way to Pakistan, with his efforts to build infrastructure in developing nations. Xi believes the world should accommodate China, not the other way around. He shows no interest in deposing North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, despite Pyongyang’s nuclear antics, and will likely respond in kind to any American trade protections, like the ones the U.S. announced for steel and aluminum in early March.

After a decade of dithering, China is also finally trying to carry out some painful and necessary economic reforms. Some of Xi’s supporters believe he needs more time and more authority to implement them. The Chinese president may realize it’s going to take a while to reduce his country’s debt, which will lead to a slowdown in growth. Maybe he wants to manage that process. This is the most optimistic view of the party’s announcement: that eventually, if the economy is humming and has a lower debt burden, perhaps Xi can hand over power to a designated successor and be remembered as a hero. Such a scenario is possible. But it assumes the Chinese leader is willing to oversee such a sustained and painful economic transition. It also assumes he’d ever give up power.

In the West, many analysts seemed jaded after Beijing’s announcement—especially those who had hoped China would reform politically as its economy prospered (just as South Korea and Taiwan had in the 1980s). These observers finally seem to be accepting reality. China is now a more confident, more repressive authoritarian state than it was before Xi. His increased crackdown on anyone critical of the government, as well as his use of internet censorship and technology to monitor citizens the regime deems troublesome, are here to stay. And may even increase.

Despite China’s economic successes, there are still millions in the country who want more political freedom. But under this regime, they have no voice—and won’t, it appears, for a long time. At 64 years old, the apparently healthy Xi isn’t going anywhere.

He’s now, most likely, China’s emperor for life.