Must Listen

- Satan's Ambition

- Counterfeit Christianity

- The Challenge Of Bible Christianity Today

- Three Men On The Mountain

- Greatest Single Issue of our Generation

- Bob Creel The Death Of A Nation

- Earth's Darkest Hour

- The Antichrist

- The Owner

- The Revived Roman Empire

- Is God Finished Dealing With Israel?

Must Read

- Mysticism, Monasticism, and the New Evangelization

- That the Lamb May Receive the Reward of His Suffering!

- The Spirit Behind AntiSemitism

- World's Most Influential Apostate

- The Very Stones Cry Out

- Seeing God With the New Eyes of Contemplative Prayer

- Is Your Church Doing Spiritual Formation? Pt. 1

- Is Your Church Doing Spiritual Formation? Pt. 2

- Is Your Church Doing Spiritual Formation? Pt. 3

- Is Your Church Worship More Pagan Than Christian? [excerpts]

- The Final Outcome of Contemplative Prayer

- The Conversion Through the Eucharist

- Frank Garlock's Warning Against Vocal Sliding

- Emerging Church Change Agents

- Emerging Church Spreading By Seasoning

- The Invasion of the Emerging Church

- Rock Musicians As Mediums (Excerpts)

- Rick Warren Calls for Union

- Does God Sanction Mystical Experiences?

- Discernment or Criticism?

- Getting High on Worship Music

- Darwin's Errors Pt. 1

- Rick Warren and Rome

- Why are There so Many Races?

- The Drake Equation

- Pathway to Apostasy

- Ironclad Evidence

- Creation Vs. Evolution

- The New Age, Occultism, and Our Children in Public Schools

- A War on Christianity

- Quiet Time

- The System of Babylon

- Is the Bible Gods Word?

- Mid-Tribulation Rapture?

- Churches Forced to Confront Transgender Agenda

- Ironside on Calvinism

- The Purpose Driven Church

- Contemplative Prayer

- Calvinisms Misrepresentations of God

- Babylonian Religion

- What is Redemption?

What Art Thinks

- The Coming of Antichrist

- The Growing Evangelical Apostasy

- Obama's Speech on Religion

- Be Ready

- Rick Warren is Building the World Church

- Spanking Children

- A Lamentation

- Worship

- Elect According to Foreknowledge of God

- Why Do The Heathen Rage

- Persecution and Martyrdom

- The Mystery of Iniquity (or Why Does Evil Continue to Grow?)

- Whatever Happened to the Gospel ?

- Quiet Time

- Divorce and Remarriage

- Ecumenism - What Is It?

- The Premillennial ? Pretribulation Rapture (2 Thessalonians 2)

- Right Now!!

- Misguided Zeal

- You're A Pharisee

- Contemplative Prayer

- NEWSLETTER Dec 2019

- NEWSLETTER Jan. 2020

- Fellowship With Your Maker

- Saved and Lost?

- Security of the Believer

- The Gospel

- NEWSLETTER April 2020

- The Believer Priest

- _Separation

- Elect According to the Foreknowledge of God

- The Preservation and Inspiration of the Scriptures

- Replacement Theology

- The Fear of the Lord

- Two Things That are Beyond Human Comprehension

- Knowing God

Pre-Millennialism

- PreTrib. Rapture

- Differences Between Israel and the Church

- 15 Reasons Why We Believe in the Pre - Tribulation, Pre-millennial Rapture of the Church

- The Pre-Tribulation, Pre-millennial Rapture of the Church

- Yet Two Comings of Christ ?

- Hating the Rapture

- Mid-Tribulation Rapture?

- The Pre - Tribulation Rapture of the Church

- The Error of a Mid-Tribulation Rapture and wrong Methods of Interpretation

- The Power of the Gospel

- Why We Believe in the Premillennial Pretribulation Rapture of the Church

Today's Headlines

- Sorry... Not Available

Locally Contributed...

Audio

- Satan's Ambition

- Counterfeit Christianity

- Three Things We All Must Do

- Two Coming Rulers

- Why No Joy

- Message Of Encouragement

- Greatest Single Issue of our Generation

- salvation.

Video

- One World Religion

- Atheism's Best Kept Secret

- Milk From Nothing

- Repentance and True Salvation

- Giana Jesson in Australia - Abortion Survivor - Pt. 1 & Pt 2

- Billy Graham Denies That Jesus Christ is the Only Way to the Father

- Emerging Church & Intersprituality Preview

- Israel, Islam and Armageddon 6 Parts

- Blasphemous Teachings of the 'emergent Church

- Megiddo 1 - the March to Armageddon

- It's Coming, the New World Order

- Creation Vs Evolution Part 1 of 4

- Creation Vs. Evolution Part 2 of 4

- Creation Vs. Evolution Part 3 of 4

- Creation Vs. Evolution Part 4 of 4

- Billy Graham Says Jesus Christ is not the Only Way

- Wide is the Gate

- A Debate: Mariology: Who is Mary According to Scripture?

- The Awful Reality of Hell

- Conception - How you are Born - Amazing

- Atheist's Best Kept Secret

- Why Kids are Becoming Obsessed With the Occult

- Searching the Truth Origins Preview 2

- Searching for Truth for Origens Preview 1

- Searching the Truth for Origins 3

- Emerging Church & the Road to Rome

- Another Jesus 1 of 7

- Another Jesus 3 of 7

- Another Jesus 4 of 7

- Another Jesus 5 of 7

- Gay Marriage is a Lie - to Destroy Marrriage

- Another Jesus 6 of 7

- Another Jesus 7 of 7

- Evolution Fact or Fiction - Part 1

- Evolution Fact or Fiction - Part 2

- Evolution Fact or Fiction - Part 3

- The Most Heartrending Abortion Testimony You ll Ever Hear, from a Former Abortionist

- Creation vs. Evolution

- A Lamp in the Dark: Untold History of the Bible - Full Documentary

- When the Trumpet of the Lord Shall Sound

Special Interest

- Will the Real Church Please Stand Up?

- Destruction of Damascus?

- Peace and Safety?

- The Emerging Church

- The Growing Evangelical Apostasy

- The State of the Church

- Child Sacrifice

- Outside the Camp

- The Church Walking With The World

- The Present Apostasy

- The World is to Blame

- How to Give Assurance of Salvation Without Conversion

- New Evagelicalism

- New Neutralism Ch. 1 - 3

- New Neutralism Ch 10-11

- New Neutralism Ch 12-13

- New Neutralism Ch 4 -6

- New Neutralism Ch 7 - 9

- The Danger of the Philosophy of New Evangelical Positivism

- Who Do Jehovah's Witnesses Say Jesus Is?

- A Dilemma of Deception: Erwin McManus 'Barbarian Way'

- Are We Fundamentalist

- Contemporary Christian Music Sways Youth to Worldly Lifestyles, Doctrinal Confusion

- The Seventh Commandment

- What will be Illegal When Homosexuality is Legal

- Christ Died on Thursday

- Military Warned 'Evangelicals' No. 1 Threat

- New Age Inroads Into the Church

- Over a Billion Abortions Committed Worldwide Since 1970: Guttmacher Institute

- The Old Cross and the New

- Is Pope Francis Laying the Groundwork for a One World Religion?

- The Goal is to Destroy all Culture and the Constitution

- E - Bomb the Real Doomsday Weapon

- The Eigtht Commandment

- Muslim Brotherhood Inside American Colleges

- Scholars Trying to Redefine Inerrancy

- In Jesus Calling: Jesus Contradicts Himself

- Jesus Calling Devotional Bible? Putting Words in Jesus Mouth and in the Bible

- How the Quantum Christ Is Transforming the World

- Creation Vs. Evolution: Could the Immune System Evolve?

- Cessationism

- Was Noah's Flood Global or Local?

- Isn't Halloween Just Harmless Fun?

- Rock Music and Insanity (Excerpts)

- Preview of the Coming of the One World Religion for Peace:

- Muslims Invoke the Name of Jesus?

- A Sin Problem Rather Than a Skin Problem

- Scientific Evidence for the Flood

- Another Step to Rebuilding the Temple - Holy of Holies Veil Being Recreated

- Darwin's Errors Pt. 1

- Eastern Mysticism

- George Muller's rules for discerning the will of God

- The Tract

- The Church and the World Deceived

- Ye Must Be Born Again

- The Call of Abraham

by PNW STAFF

September 5th, 2016

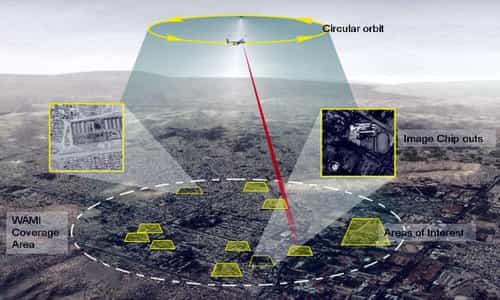

We may still have some expectation of privacy while we are in our homes, but when outside under a clear sky, there is no longer any assurance that we are not being watched, thanks to a new surveillance system being employed by the police in some cities.

First developed for the US military to monitor Iraqi cities and track those who were planting explosive devices, the technology has now been improved and applied to domestic law enforcement.

Far removed from a circling police helicopter called out for a dangerous pursuit, this system mounts a specially designed 192 mega pixel wide-angle camera array together with digital recording. It has caused a quantum leap in urban surveillance that allows police to record up to ten hours of footage that covers nearly an entire city.

The company, Persistent Surveillance Systems, based in Dayton Ohio, was started by a man named Ross McNutt. The MIT graduate founded the Center for Rapid Product Development in the Air Force. Originally tasked with creating a battlefield observation platform to track down those responsible for planting IEDs, McNutt mounted a series of six cameras on a small plane in a system dubbed Angel Fire.

With what McNutt describes as "Google Earth with TiVo capability," the system was able to record not just a specific area, but an entire city in real time. Military intelligence could watch a bomb explode then dial the time back until they watched the bomber plant it, then drive from his house.

The civilian version, now mounted in a Cessna and sporting significantly upgraded camera resolution, is being marketed to police departments around the United States and in Mexico.

The mayor of Juarez contracted the Persistent Surveillance Systems to help bring to justice cartel hit squads that were operating with impunity by tracking them back to their safe houses, but the debate has just begun in the United States where Persistent Surveillance Systems has been monitoring Baltimore for months under a blanket of secrecy.

Operating out of a nondescript office above a parking garage, McNutt and his team of pilots and analysts are under contract with the Baltimore Police Department to record the city from above. And the system works frighteningly well.

One recent Saturday, a small plane operated by an ex-Army pilot working for Persistent Surveillance Systems took to the skies with his camera system recording one image every second. He had been up for several hours when a call came through that a group of nuisance dirt bike riders, which had been terrorizing the city, had just hit and then assaulted an off duty police detective.

The police had been unable to catch the bikers for months but with the technicians now watching the images in real time, they were able to track it through the city, past street level cameras and after nearly ninety minutes, identify and arrest the riders.

In another case, a murderer left the police with little evidence until they watched hours-old footage of a figure walking away from the scene, crossing a park, entering a house and emerging to drive away in a vehicle. Both cases brought the police not only to the perpetrators but also their accomplices and linked other pieces of incriminating evidence to build strong cases.

The system works by snapping a series of incredibly high-resolution, wide-angle photos and digitally stitching them together. Up to 10 terabytes of data are stored per day and the "video" can be looked at later, zoomed in and played backwards to track the movements of suspects across the city for hours.

Individual people appear as little more than specks a pixel or two wide in the current system, but it is enough to track anyone to any location. The City of Baltimore has remained tight lipped about the project and it is unknown how many other cities have considered contracting with Persistent Surveillance Systems, except for Los Angeles, California, that recently tried the system.

Ross McNutt approached the ACLU before the project had become public knowledge, though he didn't expect the fearful reaction that his system provoked. Whereas it may be true that there is no legal expectation of privacy while out in public, the thought that our every movement is watched and recorded, ready to be played back by the police or private surveillance contractors is more than a little creepy.

Once again, a system designed in a military environment for use on a guerrilla enemy is being employed against American civilians as a tool of observation and control.

The French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote about a concept he called the panopticon in his work Discipline and Punish. The panopticon, an all-seeing presence, enforces compliance through constant observation and is the reason why prisons are now build around a central point of observation.

The citizens, or subjects perhaps, of Baltimore are now living with street corner cameras and aerial video that has built a digital panopticon that watches and records their every move, all without public consent or transparency. So the next time you are out on a city street, just look up and smile to that eye in the sky because you too might be on camera.

"Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God, and keep His commandments: for this is the whole duty of man. For God shall bring every work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good, or whether it be evil." (Ecclesiastes 12.13, 14)